When we first moved to this relatively spacious property in

Maryland just over 10 years ago I knew that I wanted to grow more native plants

that could provide food, primarily for wildlife, but also food that I might

enjoy. One of those target species was

wild or common persimmon, Diospyros

virginiana. I’ll admit that going

into this I did not have any firsthand knowledge of how to grow persimmons or

really just what they tested like.

|

An 10 year old persimmon tree, about 25' tall.

It has a nice upright form angular branching.

Fall color is yellow for my trees

|

A little internet research got me started. I learned that wildlife really liked to eat persimmons, but not until they were ripe. An unripe persimmon is loaded with tannic acid giving them an extremely astringent taste. I've tried some partially ripe persimmons and it is like having bitter sawdust in your mouth. Also when growing persimmons for harvest you need to know that they are dioecious, that is there are distinct male and female plants. You need to have at least one of each sex to get fruit. The native range for Diospyros virginiana is from New Jersey down to Florida and westward to East Texas and eastern Kansas. So Maryland is well within it native range.

|

Most female flowers are well spaced along the stem and are usually solitary. These have sterile anthers around the ovary so, superficially, male and female flowers look similar. |

|

Male flowers are more tightly packed along the stems in clusters of

1-3 at a node. The number and distribution of flowers is

a good way to tell if you have a male or female tree. |

|

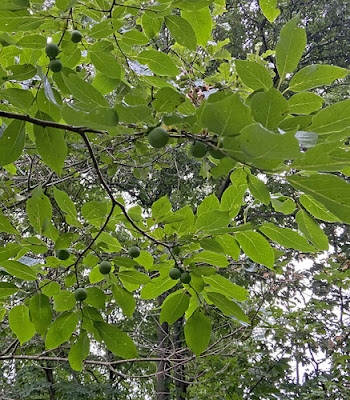

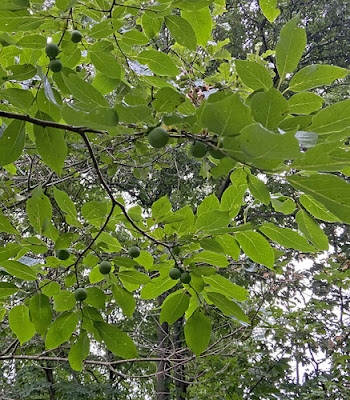

Unripe fruits are dark green and can be difficult to locate. As they ripen they turn orangey-yellow. A perfectly ripe fruit is mushy and somewhat wrinkly. |

The fruits of common persimmon are 1-1.5” in

diameter. Initially green the fruits

turn bright orange as they ripen. A fully ripe persimmon is deep orange in color and somewhat to very mushy. Around here I was picking ripe fruits from the end of September through October. While visually unappealing it tastes great and is very sweet. To me, it tastes like a mixture of very ripe

apricot and banana. Unfortunately

this means that there is a very narrow window of opportunity for harvesting

edible persimmons. A ripe persimmon is

too mushy to transport any distance in bulk.

Another less attractive feature is that they have several relatively

large seeds that hold tightly to the tasty flesh.

|

The deeply furrowed bark on this mature tree is

a distinctive feature of persimmon trees |

|

| Ripe common persimmons. Nice and mushy. The one in front is perfectly ripe. |

In a grocery store, the persimmons you are likely to find

are from an Asian species, Diospyros kaki. The most common types are Fuyu and

Hachiya. The smaller Fuyu persimmon has

seeds and is less astringent, while the larger Hachiya is seedless, but is more

astringent until fully ripe (mushy). I

did a taste comparison among these two and my homegrown common persimmons. The

Fuyu had a milder taste and was palatable even when not fully ripe. The seedless Hachiya needs to be completely

ripe (mushy) before it can be fully enjoyed. As it is seedless it has the additional advantage of having much more

edible fruit than either the Fuyu or common persimmons. Asian persimmons will ripen sitting on a counter top or, more quickly, in a bag with an apple or banana.

Of the three I found the common persimmon to

be the sweetest and most flavorful.

However, the flesh to seed ratio is very low and it, like the Hachiya,

must be fully ripe to enjoy its full flavor.

Probably the biggest drawback of the common persimmon is that it is

really not that common. It is not

commercially available and is at its best when used within a couple of day of picking.

|

| Store-bought Asian persimmons |

|

| Fuyu persimmon on left has a few seeds, the Hachiya (right) is seedless. |

So if you really want firsthand experience with common

persimmons you need to have access to a tree, a female one specifically. Growing a persimmon tree is not too

difficult. The trick is to have both a

male and female tree close enough together to allow for pollination. Common persimmon trees are classified as

small canopy trees, growing 50-75 feet in height and a spread of 35-50

feet. It has an ovoid shape. The foliage is medium textured with most

leaves being 3-4” long. The trees are tolerant of a range of soil conditions, but they need full sun. They are winter hardy to zone 5a.

When purchasing a common persimmon tree from the nursery there

is no indication whether it is a male or female plant. There is, however, one cultivar referred to as a Meader

Persimmon that is self-fertile and produces seedless fruits. The best strategy is to get at least 5 trees

and hope that you will have a mix of sexes.

For the trees that I planted it took about 5 years before they bore

flowers so that I could tell which were male and which were female. At 7 years in the ground I started getting

fruits. Of the 6 trees that I planted 9

years ago, 2 are male, two are female and two have yet to bear flowers. (One of these is in a shady location and the

other started as a 6” bare root plant.)

I took about 7 years before I began to get any fruits. Now each year the yields have been increasing

significantly.

What Now?

Now that I have invested 7 years in growing my persimmon

trees I needed to figure out what to do with them. Because of the short shelf life of wild

persimmons the best way to enjoy them over time is to preserve them in some

way. The mushy flesh of ripe persimmons

can be separated from the seeds using a food mill. The resulting pulp can be frozen for later

use or processed into jams or jellies.

There are a number of articles and videos on-line that demonstrate how

to process wild persimmons. Here’s a link to a video that I

found useful. And here’s an article from

Indiana

Public Media that describes an easy way to make persimmon jam. This year I only had about a dozen ripe fruits

at a time so I opted to make wild persimmon simple syrup that could be easily

scaled to the amount of fruit I had.

The ingredients for a persimmon simple syrup that just

highlights the flavor of the fruit are:

1 pound of persimmons

1 cup water

1 cup sugar

1 tsp lemon juice

|

| Persimmons, seeds and all are simmered with sugar and water for about a half hour |

The whole ripe (mushy) persimmons, water and sugar are

combined in a small saucepan and simmered for a half hour. I peeled the persimmons because it the pulp

slipped out of the skins so easily. (This minimized the risk of having some astringency

from the peels; however, when fully ripe the skin has no taste.) Mash up the pulp in the hot liquid several

times while simmering. After about 20

minutes, add the lemon juice. After 30

minutes of simmering allow the mixture to cool then put it into a cheesecloth

and squeeze out the nearly clear liquid.

This recipe yields about a cup of simple syrup. The remaining pulp had very little flavor

left in it. The syrup can be stored in

the refrigerator for several weeks.

|

The syrup is separated from the pulp by squeezing it

through a couple of layers of cheesecloth. |

I tried this simple syrup in several cocktails that call for

simple syrup. I found that it worked

really well in a whiskey or rum sour. I also tried it in a lemon drop recipe, but

the flavors didn’t work well together, to my taste.

Next year, assuming I will get even more persimmons maybe I'll try making a persimmon pudding.