I’ve noticed that I’ve been having less success growing vegetables from seed in my garden over the past few years. That is particularly the case for small seeded crops like lettuce and chard. This is in spite of increased organic fertilization. True, I don’t water as much as I should for seedlings, but I never do. I tend to rely on rain. Still I have become suspicious that something else may be going on. This has led me to consider allelopathy. My question is whether there is something that is growing or has grown recently in the garden is affecting the ability of new seeds to germinate and develop?

|

| Garden in mid-June: Vegetables still small in relatively clean beds, but Monardas and Rudbeckias are coming on strong. |

There are a couple of non-traditional practices that I have been employing in my vegetable garden that I am beginning to question. One is that I allow native species to run rampant along the edges and between the rows of vegetables, particularly wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) and black- and brown-eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta and triloba). The other is that I leave the roots of the previous year’s plants in place. I just cut the old plants off at ground level and throw them into the compost pile. I do this as a means of increasing the organic matter in the soil and reducing soil disturbance.

Following the adage, “a month in the laboratory can often save an hour in the library” (Frank Westheimer) I decided to do a little research first. I searched the internet for information on the allelopathic potential of all the native and non-native species that are growing in my vegetable garden. After searching those, that I turned to looking at the vegetable themselves.

The tables below list many of the weeds, native species and lastly the vegetables that are common in my garden along with the existence of any documented evidence that these plants possess any allelopathic properties.

Garden Weeds:

| Common Name |

Botanical name |

Evidence of Allelopathy |

|

Chickweed |

Stellaria media |

Yes |

|

Ground ivy |

Glechoma hederacea |

Yes |

|

Hairy bittercress |

Cardamine hirsuta |

No |

|

Indian strawberry |

Duchesnea indica |

No |

|

Mulberryweed |

Fatoua villosa |

No |

|

Ladies thumb |

Polygonum persicaria |

Yes |

|

Nut sedge |

Cyperus esculentus |

Yes |

|

Persian speedwell |

Veronica persica |

Yes |

Native Annuals & Perennials:

|

Common Name |

Botanical Name |

Allelopathic? |

|

Annual sunflower |

Helianthus annuus |

Yes |

|

Common Milkweed |

Asclepias syriaca |

Yes |

|

Butterfly weed |

Asclepias tuberosa |

No? |

|

Common and Daisy Fleabanes |

Erigeron philadelphicus and

annuus |

Yes |

|

Honeyvine |

Cynanchum laeve |

No |

|

Wild Bergamot |

Monarda fistulosa |

No |

|

Scarlet beebalm |

Monarda didyma |

Yes |

|

Purple Coneflower |

Echinacea purpurea |

Yes |

|

False sunflower |

Heliopsis helianthoides |

No |

|

Goldenrods |

Solidago sp. |

Yes (some species, at least) |

|

Browneyed Susan |

Rudbeckia triloba |

No |

|

Wild Blackberry |

Rubus sp. |

? |

|

Sealheal |

Prunella vulgarus |

No |

|

Pennsylvania smartweed |

P. pensylvanicum |

Yes |

|

Wingstem |

Verbesina alternifolia |

No* |

*Golden crownbeard, V. encelioides, a native of western North America does have allelopathic properties.

Garden Vegetables:

|

Vegetable |

Botanical Name |

Allelopathic? |

|

Arugula |

Eruca vesicaria ssp. Sativa |

No |

|

Basil |

Onicum basilicum |

Yes |

|

Collards |

Brassica oleracea var. viridis |

Yes |

|

Cucumber |

Cucumis sativus |

Yes |

|

Green Beans |

Phaseoleus vulgaris |

Yes |

|

Lettuce |

Lattuca sativa |

No |

|

Peppers |

Capsicum annuum |

Yes |

|

Squash |

Cucurbita pepo |

Yes |

|

Swiss chard |

Beta vulgaris var. cicla |

Yes |

|

Tomato |

Solanum lycopersicum |

Yes |

While doing these searches I came across some interesting studies on the potent allelopathic effects of many invasive species. This is one of the factors that allow invasive species to outcompete native ones. One study treated radish seeds with the aqueous extracts from leaves of a number of invasive species. The radish seeds were then evaluated for germination rate and root growth. The following list is ranked in order of negative effect on germination, most to least: Ailanthus altissima, > Microstegium vimineum, Alliaria petiolata, Celastrus orbiculatus,> Ligustrum vulgare, Rosa multiflora, Rubus phoenicolasius, and Acer platanoides. There are multiple studies that document the allelopathic effects of Japanese knotweed, Polygonum cuspidatum. It seems that many species of the genus Polygonum have some allelopathic character.

From this research it looks like the fleabanes (Erigeron annuus and philadelphicus) and purple coneflower would be the most likely allelopathic culprits among the native species in my garden. However, most of the allelopathic candidates on these lists are from the weeds and garden vegetables. Of these, ground ivy, nut sedge and ladies thumb are the most prolific weeds in my garden. Among the vegetables in my garden, collards, peppers and cucumber are the most likely suspects to be causing some troublesome effects.

Allelopathy experiments. In general experiments that measure allelopathy are tricky to interpret. Many are based on bioassays, where the allelopathic effect is measured by such things as the germination rates and root growth of a target species. In many cases radish or lettuce seeds are used. Many of these studies use extracts of leaves, stems or roots of the species being studied applied at various concentrations to isolated seeds of the target species in a Petri dish. Another approach is to test the soil itself. Due to the complex nature of plant-soil and plant-plant interactions, most studies on allelopathy are correlative rather than causative.

To help me understand whether there was a problem with the soil (and all the things that come with it), or the cultural effects like moisture and sunlight, I decided I would try a bioassay comparing surface soil samples from various parts of the yard and garden. I tested to see how each of these soils affected germination and growth of some lettuce seeds which had performed well when started indoors this past spring.

|

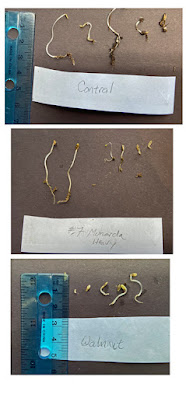

| Germinated seeds: Control (top); near wild bergamot (middle); under English walnut (bottom) |

After five days I separated out the germinated lettuce seeds, counted the number of germinated lettuce seeds and measured the length of the roots. I found I was able to pluck out the germinated seeds from the soil in the baggies by suspending the entire sample in water with a little dish soap. This allowed the soil to fall away from the roots without damaging them. The root growth measurements had a lot of variation. This is not too surprising considering the many uncontrolled variables, like variable soil moisture and soil contact within each baggie, and small sample size.

|

| Graphical comparison of various soil samples on germination and root growth of 'New Red Fire' lettuce seeds. |

Results and Conclusions

While the differences in root length and germination rate among these samples are not highly significant, due to the small samples size, there is an indication that the soil around the collards is not as favorable to seed germination and growth as any of the other garden samples and is on the order of that for soil under an English walnut tree. (English walnut, Juglans regia, is much less allelopathic than our native black walnut.) These results also indicate that the presence of wild bergamot (Monarda) is not detrimental to the initial stages of seed growth. Another indication was that root growth in the soil around the green beans was less than the control sample. This is consistent with a study that looked at the effect of leaf extracts of several lines of common beans on seedling growth, including lettuce. That study made no mention of the effect on seed germination.

Lettuce or radish seed bioassays are also good for checking for herbicide residues in soils and mulches. General information about testing whole soil samples for herbicide residues can be found at this link from NC State.

Based on the literature it seems like many of the plants in my garden have some degree of allelopathic behavior. This brings up another important question; how long does that effect last. The sense I get is that it’s more on the order of weeks than months. In field trials some brassica family cover crops have shown allelophatic effects on the order of weeks to months after being tilled in. I found another post discussing the use of cover crops, many of which are allelopathic. It suggested waiting 3 weeks after tilling them in before planting. Leaving allelopathic plant residues in place as a mulch, will increase the time over which they have the suppressive effect.

Another less traditional garden practice I have been using is flame weeding. This involves using a hand-held propane torch to kill weed seedlings before they can establish. This was done prior to planting, or transplanting crops. An advantage of this practice is that it doesn’t disturb the soil surface. I have not looked into any literature on possible negative effects of this practice, but for next year I will not use this method in the growing beds themselves.

So with these changes we will see if I get any better results in the garden, or will I need to dig deeper?